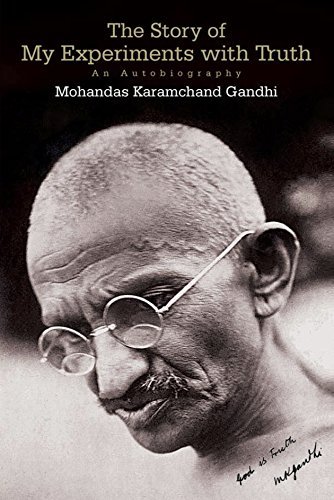

The Story of My Experiments with the Truth

Rating: 4.5/5

Author: Mahatma Gandhi

Publisher: Navajivan Mudranalaya

Publishing Date: 1927 (originally published)

Language: English

Genre: Autobiography

ISBN-10: 8172343116

ISBN-13: 978-8172343118

Format: Paperback

Pages: 448

Cost: Rs. 139 (Paperback), 982 (Hardcover), 114.98 (Kindle edition)

Plot:

This unusual autobiography “The Story of My Experiments with Truth”, is a window to the workings of Mahatma Gandhi’s mind – a window to the emotions of his heart- a window to understanding what drove this seemingly ordinary man to the heights of being the father of a nation- India.

Starting with his days as a boy, Gandhi takes one through his trials and turmoil and situations that moulded his philosophy of life- going through child marriage, his studies in England, practicing Law in South Africa and his Satyagraha there to the early beginnings of the Independence movement in India.

He did not aim to write an autobiography but rather share the experience of his various experiments with truth to arrive at what he perceived as Absolute Truth- the ideal of his struggle against racism, violence and colonialism.

Review:

The Story of My Experiments with Truth is the autobiography of Mohandas K. Gandhi, covering his life from early childhood through to 1921. It was written in weekly instalments and published in his journal Navjivan from 1925 to 1929.

In Gandhi’s autobiography, one can find the idea that life is nothing but a spiritual experience with truth, and a struggle against all forms of untruth and injustice.

As such, Gandhi claimed that his life was his message, simply because he extended his practice of satyagraha to all walks of life. Gandhi, in short, was a leader looking for a spiritual cause. He found it, of course, in his non-violence and, ultimately, in independence for India. Truth, Satya, was the central axis of the Gandhian system of thought and practice.

For Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, everything turned on Truth- satyagraha, swaraj, ahimsa, ashram, brahmacharya, yajna, charkha, khadi, and finally, moksha itself.

“Truth is not merely that which we are expected to speak and follow. It is that which alone is, it is that of which all things are made, it is that which subsists by its own power, which alone is eternal.”

In his Autobiography Gandhi makes the same point without, of course, dishing out the paraphernalia and minutiae of cost analysis that Fakir Mohan is able to supply from his intimacy with the ground reality.

Gandhi learned 11 languages throughout his life, including his native Gujarati. He used his knowledge of other languages to connect with others on a deeper level, helping them fight for human and civil rights. He believed that all children should learn more than one language.

He says “It is now my opinion that in all Indian curricula of higher education there should be a place for Hindi, Sanskrit, Persian, Arabic and English, besides of course the vernacular.” (Gandhi, 1948, p. 9)

For Gandhi, language learning and leadership were intertwined. He saw language learning as a way to communicate with others in his own country, to connect with others on a deeper level, understanding their human condition from a compassionate point of view.

An alternative perspective on life that was promoted by Gandhi was one where life is a series of experiments. An experiment is defined as a success if something is learned as a result of an experiment. The only time an experiment fails is if there is no learning. When that happens, the experiment is repeated until there is learning and new experiments can be performed based on what was previously learned.

Gandhi applied this perspective of life as an experiment to all aspects of his life. The word “experiment” is used over 95 times in his 160 brief chapters. He applied the concept to topics such as spirituality, parenting, education, morality, medicine and more.

Gandhi was aware of how his body and mind were responding to his experiments. He was able to apply seemingly mundane experiments in areas such as learning how to iron collars and how to dance into personal development opportunities. Again using his experiments in diet, he was able to identify changes in his thinking as a result:

“I stopped taking the sweets and condiments I had got from home. The mind having taken a different turn, the fondness for condiments wore away, and I now relished the boiled spinach which in Richmond tasted insipid, cooked without condiments. Many such experiments taught me that the real seat of taste was not the tongue but the mind.”

The book will teach you how learning more about the world and those who live in it leads to deeper understandings of other cultures, other values and other ways of understanding life, love, politics, spirituality and all that is important to humans. Learning other languages opens up new possibilities for personal and professional growth, new opportunities to do meaningful work and ultimately, to value others more deeply because we can communicate with them better and understand them.

Finally, in ‘The Story of My Experiments with Truth’, Gandhi displays an admirable dedication to morality and ethics- from honesty to vegetarianism, from keeping vows to self-denial, all of these that reveal the depth of Gandhi's commitment to doing what he believes is right!

About the Author:

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was an Indian freedom fighter, lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethicist, who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful campaign for India's independence from British rule, and in turn inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world.

Gandhiji completed his law in England and came back to India in 1893. He started his career as a lawyer. He supported the poor and truthful clients. He went to South Africa to deal with the cases of a Seth Abdula one of the famous merchant.

In South Africa he fought against many troubles. Gandhiji fought against this unjust and cruel treatment. He observed Satyagraha there and became successful. In South Africa he built up his career as a Satyagrahi. He returned to India in 1915.

In India, he observed Satyagraha in Champaran and Borsad. He had started Dandi March on 12th March 1930 from Satyagraha ashram from Ahmedabad with 78 other people to Dandi to break the law of salt and became successful in doing so. He was sent to jail many times. He started the Non-co-operation in 1930 and the Quit India Movement in 1942. He became famous as the ‘Father of Nation’ and at last India wins freedom on 15th August 1947.